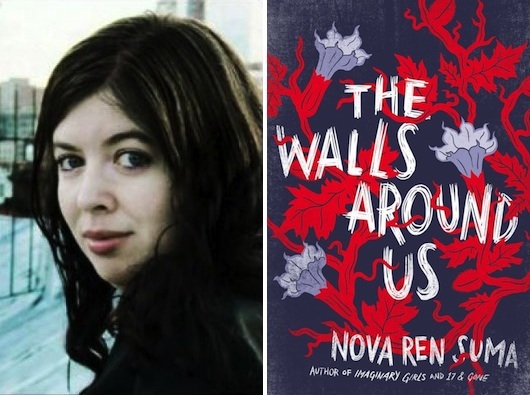

Critical darling Nova Ren Suma is already well-known for her gorgeous, genre-hopping, and distinctly sinister body of work. We talked about memory, ghosts, and unreliable and monstrous girls in advance of the March 23rd publication of her newest novel, The Walls Around Us, which is already garnering rave reviews.

Sarah McCarry: All of your books deal with unreliable narrators, ghosts, and the complexity of memory. Can you talk about how those elements intersect for you, and what draws you to them?

Nova Ren Suma: I love seeing my books’ recurring themes distilled in this way… I didn’t realize. Or at least I haven’t been doing it so consciously. It’s just what I’m drawn to writing. Unreliable narrators feel most honest to me. Maybe it’s because I don’t trust many people and I don’t always believe what people tell me. And I find myself so fascinated with the way memory distorts and can’t be trusted, either. As for ghosts, well, stories involving otherworldly elements stepping into the everyday is my favorite thing. The line between real and fantasy has been blurred to me since I was a child. Even now, when I set out to write a completely “realistic” story, something surreal or fantastical steps in, and feels just as real as everything else. I’ve just decided to embrace it.

SM: I think writing about adolescence lends itself well to that blurriness, too—I don’t know if it’s true for everyone, but I definitely felt that the boundaries between the “real” world and the invisible were much more permeable when I was a teenager. And it’s interesting to think about ghosts as just a different kind of memory. You started out writing fiction for adult audiences—were those themes in your work with adult characters, too?

NRS: Certainly unreliable narrators found themselves in my two (unpublished) adult novels, yes. And the distortion of memory was a huge theme in the second one especially. But ghosts and otherworldly elements didn’t come in until I began writing my first YA, Imaginary Girls, which was published in 2011. I was taking a leap and reinventing myself as a writer with that book, and it wasn’t just the YA part of it. Before that, I never wrote anything fantastical. Now I can’t stop. It felt so freeing.

SM: The Walls Around Us deals explicitly with the ways in which girls can be monstrous, particularly to each other. What’s the most enjoyable—and the most difficult—part for you of writing about monsters?

NRS: My intent with this book, in the early days when I was playing around with ideas, was simply that I wanted to write about “bad” girls who do bad things. I wanted to write from that perspective, to own it, to understand it, to face it without censor. That was the spark that led me here, and also gave me the perspective of seeing the story through their eyes and living in their skin. I hope, if some of these girls do monstrous things and get locked up for it, this story explores why and shows what comes after. Who, really, is guilty? And who, really, is innocent?

For a long time I found myself circling around writing the worst things—a bloody murder, say—kind of like holding my breath and pausing too long before dunking into a cold pool of water. But then I went for it, and the hardest part was stopping myself, and getting out. I could have gone deeper. I might still, in a new novel. I guess this experiment in writing about monstrous things only made me want to write more of them.

SM: I find monsters quite addictive as well. They seem to have a lot more fun.

Whose story did you start with—Violet’s, Ori’s, or Amber’s? When did they start to come together for you?

NRS: This may not be a surprise because there are two different POVs in The Walls Around Us, but this book started out as ideas for two separate novels. The first idea was about teenage killers, young ballerinas on the run. This was the seed of Violet’s (and Ori’s) side of the story. A little after this, I put that aside and began developing an idea for a ghost story that took place in a girls’ juvenile detention center, and this was the seed of Amber’s side of the story. I got a shiver up my spine one day when I realized the stories could connect and feed off each other and tangle and intertwine. It began with Amber. I was sketching out a rough scene in which a new young prisoner stepped off the bus and looked up at the Aurora Hills Secure Juvenile Detention Center for the first time, while the girls inside the detention center were looking down and guessing at who she might be, and I realized who that girl was. I knew her. It was Ori. That’s when the two novels I thought I was playing with turned into one solid thing.

SM: The Walls Around Us is beautiful, but it’s often a difficult book to read, and I imagine it was a difficult book to write. How do you balance out writing a world that’s not exactly the easiest place to spend a lot of time with the rest of your life? Did you find yourself haunted by the book when you weren’t working on it?

NRS: I found myself obsessed with the world of this detention center—so, yes, I was haunted. But the funny thing about this book is how much it took me over, and consumed me and eventually lifted me up with inspiration. I think it’s because while writing this book I gave up on expectations and what other people might want from me. I wrote this solely for myself. In a way, it was the easiest book to write because of that, because I’d stopped worrying so much, and embraced how strange the story was going to be and allowed myself to write it with the language I wanted and the intersecting timeline I wanted. There is so much of me in here, but it’s veiled and distorted and most readers would never know. Of course now that writing this book is over, I’m working on something new and worrying myself into a stupor all over again. I miss the freedom of writing about a haunted prison. The irony.

SM: I find that so interesting, because I see this idea being circulated that it’s somehow a betrayal of the “audience,” whoever that may be, or an elitist ideal, to assert that an artist’s first loyalty is to the work and not the reader, and I can’t help also reading that cultural suspicion as gendered. Women aren’t supposed to give up worrying about other people’s expectations and I think women writers are more likely to be seen as “owing” something to an audience, especially if they’re being published in genre fiction. The practice of making art demands a kind of selfishness that I see as essential, but that women certainly aren’t supposed to embrace. Do you think that’s true as well, or do you see writing as something more—I don’t know, interactive, I guess, for lack of a better word?

NRS: I do think there’s this expectation that I should write first for my readers, and that I should be aware of audience, especially as a YA writer whose target readers are meant to be teens. This is something I may have absorbed as a woman, too, to put others first and never myself. I can’t do it when it comes to my writing. I tried writing for readers’ imagined expectations and it ruined writing for me. It made me question everything. (There’s a post on my blog about coming to terms with this while writing The Walls Around Us, which then led to an episode of Sara Zarr’s podcast “This Creative Life.”) It came from a need to find a way to love writing again after tunneling into a pit of doubts.

It may be selfish, but just being a novelist in itself—when no one else on either side of my family was an artist… no one could afford to do such a thing, most especially the women—feels like an outrageous pursuit. A career I am not supposed to have. Yet here I am, defying the idea of being practical and doing it.

SM: Your books are published as YA, though in many ways they read more like literary adult fiction that happens to be about teenage girls. Do you struggle with that tension? What are the most valuable parts for you of being published as a YA writer, and what do you find frustrating?

NRS: Before I published YA novels, I was writing fiction for adults. That’s what I focused on while getting my MFA in the late 1990s before YA was as big as it is today, and it’s what I always held dangling out before myself, my dream. I tried to get an agent with two adult novels over the years and failed. Both of those novels were told from young voices. I hit a very low point and considered giving up on trying to publish. Then, through a long story involving working a day job in children’s book publishing, the world of YA opened its doors to me and gave me an opportunity. I leaped at it. I’ll always be grateful for what felt like a second chance.

Even so, I’ll admit I’m not writing with this specific audience in mind. I’m writing about teenage girls—always girls, I’m most interested in the complicated and threatened and powerful lives of girls—but my books aren’t necessarily just for teenagers. They’re for anyone who wants to read them, and I know the YA label scares some prospective readers away. Sometimes I wish my books could be published without a label and shelved in the YA section and also shelved in the adult section, or that there could even be two editions. The story inside would be the same, but sometimes—though not in the case of the gorgeous The Walls Around Us art!—the covers might be different.

Most of all, I do see my books as YA. That’s because I see the category of YA as an ever-changing, exciting, fiery and alive place where there is room for books like mine because there is room for so many things. So many. I think it’s a matter of expanding the definition of what can be a YA novel, and then also rethinking who can be the audience for YA. If only the rest of the literary world saw it this way…

SM: Amen to that!

Sarah McCarry is the author of the novels All Our Pretty Songs, the Norton award-nominated Dirty Wings, and the upcoming About A Girl, a book with no shortage of girl monsters.